Chapter 08

Charge and Magnetism

Charge is a concept that we may at first think is well understood and not requiring further investigation. As a source of the electric field, physics only says it is an intrinsic property of certain elementary particles and that it can neither be created nor destroyed. Its fixed absolute value is either positive or negative in whole integer amounts, although somehow it allows quarks to disobey this. Additionally, like charges repel each other and unlike charges attract, because of the electromagnetic force which manifests due to the action of charge. The physics we follow today was originally conceived by scientists such as Faraday and Maxwell in the 18th century. So much of our current technology relies on these ideas, that it is difficult to imagine a world without these concepts. But is this a simplification of a deeper truth?

We tend to believe that charge is like a basic unit or grain of static electricity. It cannot be divided below a certain value, as Millikan showed in 1909, with his experiments on the electron and his verification of its elementary charge. We know we cannot have half an electron, likewise half a unit of charge.

It also happens that the proton has an equal and opposite unit of this absolute charge, and furthermore that both electrons and protons have antiparticle pairs that have opposite charge, although why should this be so? No other values other than these two have ever been confirmed in experiments, not even for quarks. However as soon as we focused and tried to define charge accurately, its true meaning became slippery and elusive. Like time, there were no real counterparts for the definition of charge.

And what about magnetism? This is something most people associate with compass needles and fridge magnets. Some kind of gluey stuff that can attract or repel without actually touching anything.

While we don’t often get the opportunity to directly experience static electric charge, other than possibly with a plastic comb pulling slightly on our hair, a magnet is something we’ve all played with and felt its invisible force act in space. For some people, especially children, it is so real and tangible yet wonderful and fascinating. But how can a magnet do that and what makes our hair stand up straight? Once again, the answer lies in the structure of our roton and the spin or angular momentum of its electromagnetic fields.

Angular momentum in the sense that charge and magnetism are directly caused by fixed genuine spin. Like night and day being directly connected to angular momentum on earth, due to its constant spin and light from the sun. Sometimes there is a direct connection between what were once considered unrelated ideas. For instance, we now know that temperature is a measure of atomic and molecular vibration, but science did not originally suspect this. However, many things are like that, and we now know this is especially true of electricity and magnetism. For they are intimately connected to each other, even more so than physics currently suspects. Our model shows how.

This book proposes a new approach to our understanding of how these two things were created and what it means to physics. It follows from papers originally written by me, as well as Qui-Hong Hu (The Nature of the Electron [1]) and Williamson and Van Der Mark (Is the Electron a Photon with Toroidal Topology? [5]). I thank them again for their contribution and diagrams included here.

The origin of charge

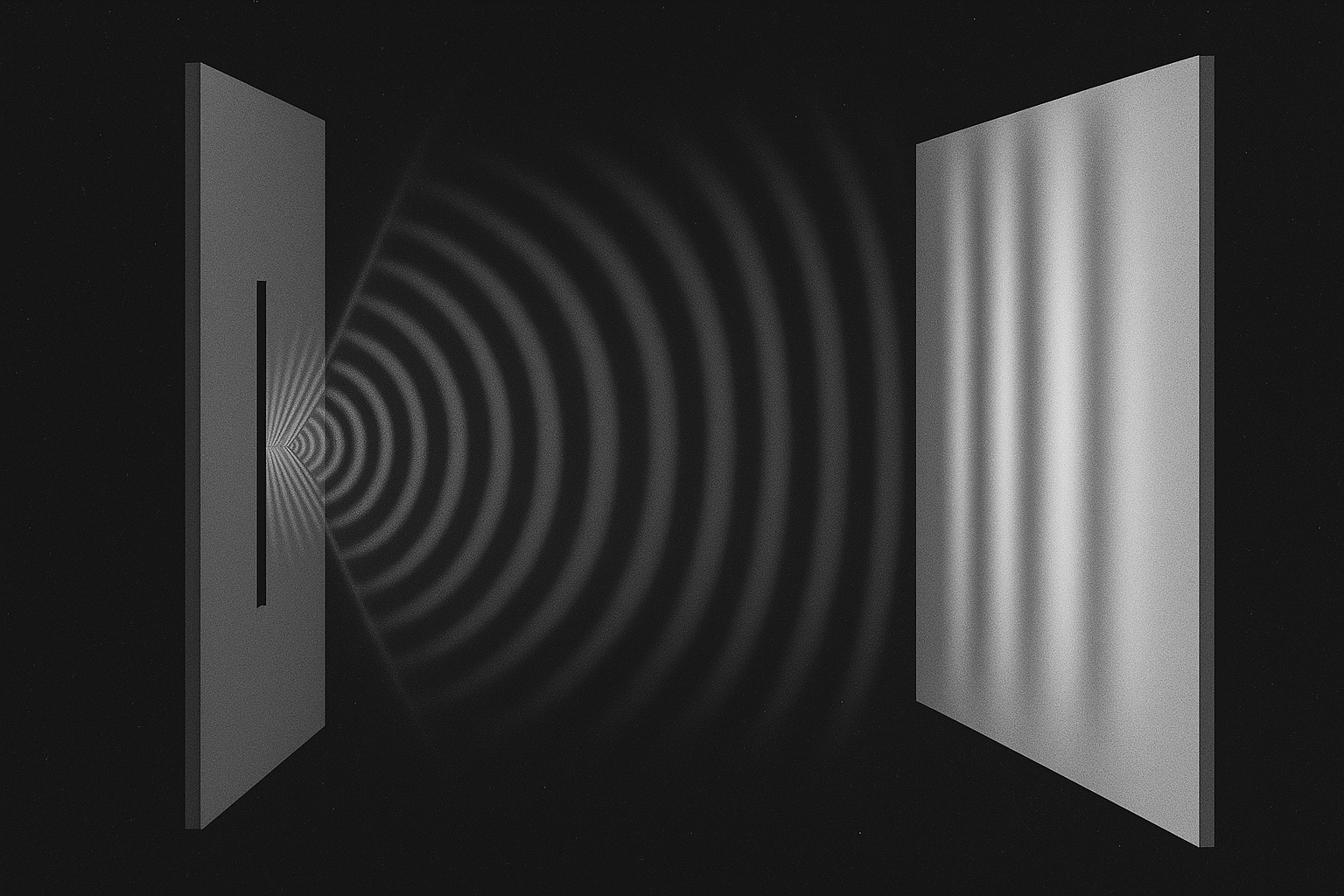

A photon consists of rapidly rotating electric and magnetic fields in two dimensions, creating each other as it moves in a straight line through space at speed c. It moves in a kind of helix or spiral, but it has no charge because its flat circular shape means the two half cycles of electric field have opposite phase and orientation in space-time and so cancel each other out after each full wave. This is not the case though for the rotons of charged particles.

It may help to understand how, if we imagine twisting the second half cycle of a wave upside down. This twist turns a crest and a trough into two crests or two troughs, depending on its direction, clockwise or anticlockwise. Similarly, our model shows that a roton creates either inward or outward fields from a twisted E-M wave. (Note: As we often say, a demonstration model such as the marked-up strip is a very useful aid in following this explanation).

Fundamental particles are 3-D solitons that have a roton in their structure. It is this unique shape with its two loops created through angular momentum and twist that makes charge and magnetism. Moving from one loop to the next, the electric and magnetic fields turn back on themselves, as they conserve their spin. Each loop consists of a half-cycle that inverts the phase of the fields after every full rotation. Consequently, their fields signs (i.e. +ve or -ve) with respect to space do not change or become opposite like those of the flat photon. They still generate each other and behave according to Maxwell's equations yet remain confined in space with a permanent sense both pointing continuously inward or outward from their hemisphere, creating positive or negative charge. This continues unabated for the life of the soliton.

Figure 12 - A photon moving in the Roton or Hubius Helix path creates charge. Modified from Williamson and Van Der Mark

The top drawing here in Figure 12 shows a single cycle of a normal E-M wave, then, with the effect of a 360º clockwise twist drawn below it. Due to this twist, our model shows that the E-field is always pointing inward at 90° to the path's motion (opposite or out for an anticlockwise twist), thus giving it what we call charge, here shown in the lowest drawing as the up and down E-field arrows, both pointing inward (outward for opposite twist in antiparticles). This is divergence as the field emanates either in or out of a tiny, closed surface and it shows that the roton’s spinning E-field creates charge and not vice versa.

Charge can only form in a roton with its unique shape that turns the field back on itself, twice each cycle. Consequently, any fundamental particle that has a roton in its structure may possess charge. However, this initial twist could have been reversed creating an antiparticle with opposite charge, but once formed, this can never change. All other properties of particle and antiparticle remain the same.

Note: A neutron is an exception and displays no charge because probability allows two virtual yet opposite rotons to form its soliton and these cancel out this effect, as shown later in the section on the atom.

This means that what we call charge and magnetic moment are actually constructs of the standing E and B-fields, always oriented either in or out though the soliton and into space.

So, charge is the result of the (1)rapid and sustained vibration of the E-field’s standing wave over the same tiny continuous path. It is not a thing in itself, but actually the ratio of the force and the electric field strength that produces that force. This ratio can never change and that is why it is a constant or absolute.

Thus, our model shows that there is no need to hypothesise that charge is an intrinsic property of a point particle, with all the difficulties such an approach entails. Here charge comes about naturally, due to the ongoing behaviour of the E-M field trapped in our soliton The E-field emanates either in or out of the roton, always being in the same direction in both loops. This creates a permanent positive or negative charge, due to the divergence of the E-field. The twist can be either clockwise or anticlockwise but can never change once a particle is created. This is how charge is conserved. The twist is due to the Fine Structure Constant, or α, and has a value of plus or minus αh, depending on spin direction. In units of h it is α or ~137th of Planck’s Constant. A very small number and a very unlikely number. In the soliton, the normally straight-line path of the field is curled by αh once per cycle. Small and unlikely indeed. But that’s all it takes. And it’s so unlikely that it’s impossible to copy. We only have as many as were created in the Big Bang.

This gives us a structural basis for two of Maxwell’s laws. The first law concerns divergence, meaning that if an electric field emanates from an enclosed surface, that surface must contain a charge. Here we invert this principle and say that yes, we have a charge, but it is created by fields. The second law states that a magnetic monopole cannot exist. SED agrees and contends that there are always two loops inside a roton, with the magnetic field passing through both and forming two opposite poles. This is magnetism and it is created in the roton, as we will discover now.

The origin of magnetism

All magnets are dipoles, and by definition, a magnetic dipole must have two opposite poles separated by a certain distance. Our SED model explains how magnetism arises through the structure of the roton and that magnetic poles, like charge, are a consequence of the soliton’s dynamic field structure and not a cause.

If we examine Figure 13 below, we see that magnetic field direction is opposite in each loop. This creates two different poles, that we call Nth and Sth. Each loop acts as a magnetic monopole but cannot exist independently. We always have two. Furthermore, using geometry, if the radius of a loop is r, then the centres of each loop are separated in space by r√2. Thus, we have a dipole with a fixed magnetic moment. The roton creates a permanent magnet and all fundamental particles have a magnetic moment that can exist in either one of two opposite states, due to the two different magnetic directions through the soliton.

Only with an external interaction, is it possible to change the state of a roton by turning it inside-out, like inverting an umbrella. We find this reverses the magnetic field direction but not its charge, for this is always conserved.

Magnetic attraction from opposite poles makes the path bend at its centre with a specific angle of 90° between the loops. This gives the soliton the shape of a bent lemniscate draped over a hemisphere, as shown in the introduction above. We will see later how this gives rise to gravity.

Figure 13 – Roton view from above

Figure 14 – Roton viewed end-on or side view

It is interesting to observe our model from different orientations. If we look at it from above, field energy flow is clockwise in one loop and anticlockwise in the other. From this perspective, the right-hand rule for magnetism means that their poles are opposite or Nth in one and Sth in the other. Viewed end on, we find field rotation appears to spin in the same direction in each loop. That is, either both clockwise or both anticlockwise, thus providing a continuous magnetic field direction through the loops and giving the particle an overall magnetic moment.

How charge works according to fields

In the following discussion and due to the importance this book places on fields rather than their consequence, charge, it may be necessary to restate a common rule of physics and bring it in line with these new insights. The rule has always been: Equal charges repel, and opposite charges attract. A better statement would be: Equal fields attract, and opposite fields repel. The next diagram explains why this is so.

Figure 15 - Electromagnetic forces are due to the fields interactions in space and not charge centres themselves.

The diagram above shows that attractive and repulsive forces actually arise between charged particles due to the interaction of the electric fields in the space surrounding them. It is not due to the particles or charges themselves. The field’s interaction is the inverse of what we normally associate with charge: That is, equal fields attract, and opposite fields repel.

Equal fields (i.e. those having the same direction and magnitude in space) are found in the space between two opposite charges. This causes attraction because the energy flow in each soliton is spinning in the same direction. Thus, there is no conflict with their relative spin speed exceeding c, and they attract each other. The reverse is the case for equal charges, when this relative flow direction is opposite between them, and so close charges repel to avoid a conflict with the maximum speed of light. All this will be explored in greater detail in the upcoming section on the atom.

We need to repeat that charge is not in itself a force, just the measure of a constant ratio: the strength of force to field. That is why the proton’s charge is the same as the electron’s despite the fact that, due to its greater mass, its fields and associated forces are both many times bigger. Inside the nucleus, they are nearly 3.4 million times larger than those of an electron, but the force to field ratio (i.e. charge) stays constant for both. Consequently, the forces are huge and there is an enormous amount of energy locked up inside the nucleus compared with the rest of an atom.

It is also the reason why quarks cannot exist - fractional charge is not possible. How could this ratio change? Quarks were only hypothesised to try and explain the anomalous magnetic moment of nucleons and for some time had no opposition. But SED has a possible answer for this anomaly and consequently has no need for quarks anyway. We discuss this further in ‘the atom’ chapter and ‘problems with the standard model’ chapter.

Fields and magnetism

Referring back to figure 12 above, we see that while the electric field always points either into or out of both loops of the roton, the magnetic field is opposite in each loop no matter what the direction of spin. One loop creates what we call a north pole and the other a south pole, with a fixed distance separating them. This forms a magnetic dipole, and all magnets are dipoles. The roton is the ultimate structure that provides the root cause for magnetism, through the action of its fields. Always with two opposite loops, it is also the physical reason why magnetic monopoles can never exist. Rotons cannot be cut in half. The fundamental E-M wave forming them is a kind of quantum that always has two opposite components in one cycle. Like endless Yin and Yang.

So, we see that the electric field has diversion because it points in the same direction, either into or out of the roton in each loop. According to Maxwell’s laws it therefore acts as a source of charge. However, for the magnetic field, this diversion is zero due to opposite poles in each loop. Magnetic field lines circulate outside the roton from the north pole to the south but continue internally from south back to the north pole. They are continuous with no source or beginning.

Like electric charge, there is no thing called a magnetic dipole that exists in and of itself. It is simply a construct of the E-M field existing in its two opposite states, just like everything else is. Its basic or minimum value is the Bohr Magneton which is described and calculated in the next section on the electron.

(1) The path is so small and the frequency so high, that the resulting charge appears constant. However, it can portray a tiny trembling effect, known as Zitterbewegung, that can be picked up in sensitive experiments.

The Origin of Everything

(Online Edition)